This is the mobile-friendly web version of the original article.

Best Practices for MITRE ATT&CK® Mapping

Publication: June 2021

DISCLAIMER: This document is marked TLP:WHITE. Disclosure is not limited. Sources may use TLP:WHITE when information carries minimal or no foreseeable risk of misuse, in accordance with applicable rules and procedures for public release. Subject to standard copyright rules, TLP:WHITE information may be distributed without restriction. For more information on the Traffic Light Protocol, see http://www.cisa.gov/tlp/.

- INTRODUCTION

- MAPPING MITRE ATT&CK INTO FINISHED REPORTS

- MAPPING MITRE ATT&CK INTO RAW DATA

- APPENDIX A: RESOURCES5

- APPENDIX B: EXAMPLE REPORT INCORPORATING ATT&CK

- TrickBot Malware

INTRODUCTION

For the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), understanding adversary behavior is often the first step in protecting networks and data. The success network defenders have in detecting and mitigating cyberattacks depends on this understanding. The MITRE ATT&CK® framework is a globally accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations. ATT&CK provides details on 100+ threat actor groups, including the techniques and software they are known to use.1 ATT&CK can be used to identify defensive gaps, assess security tool capabilities, organize detections, hunt for threats, engage in red team activities, or validate mitigation controls. CISA uses ATT&CK as a lens through which to identify and analyze adversary behavior. CISA created this guide with the Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute™ (HSSEDI), a DHS-owned federally funded research and development center (FFRDC), which worked with the MITRE ATT&CK team.

ATT&CK Levels

ATT&CK describes behaviors across the adversary lifecycle, commonly known as tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). In ATT&CK, these behaviors correspond to four increasingly granular levels:

Tactics represent the “what” and “why” of an ATT&CK technique or sub-technique. They are the adversary’s technical goals, the reason for performing an action, and what they are trying to achieve. For example, an adversary may want to achieve credential access in order to gain access to a target network. Each tactic contains an array of techniques that network defenders have observed being used in the wild by threat actors. Note: The ATT&CK framework is not intended to be interpreted as linear—with the adversary moving through the tactics in a straight line (i.e., left to right) in order to accomplish their goal. 2 Additionally, an adversary does not need to use all of the ATT&CK tactics in order to achieve their operational goals.

Techniques represent “how” an adversary achieves a tactical goal by performing an action. For example, an adversary may dump credentials to achieve credential access. Techniques may also represent what an adversary gains by performing an action. A technique is a specific behavior to achieve a goal and is often a single step in a string of activities intended to complete the adversary’s overall mission. Note: many of the techniques within ATT&CK include legitimate system functions that can be used for malicious purposes (referred to as “living off the land”).

Sub-techniques provide more granular descriptions of techniques. For example, there are behaviors under the OS Credential Dumping [T1003] technique that describe specific methods to perform the technique, such as accessing LSASS Memory [T1003.001], Security Account Manager [T1003.002], or /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow [TT1003.008]. Sub-techniques are often, but not always, operating system or platform specific. Not all techniques have sub-techniques.

Procedures are particular instances of how a technique or sub-technique has been used. They can be useful for replication of an incident with adversary emulation and for specifics on how to detect that instance in use.

1. Not every adversary behavior is documented in ATT&CK.

2 For example, after Initial Access [TA0001] and during an operation, the adversary may exfiltrate data (Exfiltration [TA0010]) and then implement additional persistence mechanisms (Persistence [TA0003]), switching tactics from right to left.

ATT&CK Technology Domains

ATT&CK is organized in a series of “technology domains” – the ecosystem within which an adversary operates. The following are ATT&CK knowledge bases for specific domains that have been developed or are currently being developed:

MITRE ATT&CK - Enterprise3:

- Platform-based: Windows, Linux, and MacOS environments

- Cloud Matrix: AWS (Amazon Web Service), GCP (Google Cloud Platform), Azure, Office 365, Azure AD, Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) platforms

- Network Matrix: Network infrastructure devices

MITRE ATT&CK - Mobile: Provides a model of adversarial tactics and techniques to gain access to Android and iOS platforms. ATT&CK for Mobile also contains a separate matrix of network-based effects, which are techniques that an adversary can employ without access to the mobile device itself.

MITRE ATT&CK - Industrial Control Systems (ICS): Focuses on adversary tactics and techniques whose primary goal is disrupting an industrial control process, including Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, and other control system configurations.

ATT&CK Mapping Guidance

CISA is providing this guidance to help analysts accurately and consistently map adversary behaviors to the relevant ATT&CK techniques as part of cyber threat intelligence (CTI)—whether the analyst wishes to incorporate ATT&CK into a cybersecurity publication or an analysis of raw data.

Successful applications of ATT&CK should produce an accurate and consistent set of mappings which can be used to develop adversary profiles, conduct activity trend analyses, and be incorporated into reporting for detection, response, and mitigation purposes. Although there are different ways to approach this task, this guidance provides a starting point. Note: CISA and MITRE ATT&CK recommend that analysts first become comfortable with mapping finished reporting to ATT&CK, as there are often more clues within finished reports that can aid an analyst in determining the appropriate mapping.

For additional resources on learning about and using the ATT&CK framework, see Appendix A. For an annotated example of a published CISA cybersecurity advisory that incorporates ATT&CK mapping, see Appendix B.

3 ATT&CK Version 8 integrated PRE-ATT&CK techniques into ATT&CK for Enterprise creating the new Reconnaissance and Resource Development tactics. The PRE-ATT&CK matrix was deprecated and although it remains in the knowledge base, it will no longer be updated. See ATT&CK blog: Bringing PRE into Enterprise, (October 27, 2020).

MAPPING MITRE ATT&CK INTO FINISHED REPORTS

The steps below describe how to successfully map CTI reports to ATT&CK. Analysts may choose their own starting point (e.g., identification of tactics versus techniques) based on the information available and their knowledge of ATT&CK. Appendix B provides an annotated example of a cybersecurity advisory that incorporates ATT&CK.

Find the behavior. Searching for signs of adversary behavior is a paradigm shift from looking for Indicators of Compromise (IOCs), hashes of malware files, URLs, domain names, and other artifacts of previous compromise. Look for signs of how the adversary interacted with specific platforms and applications to find a chain of anomalous or suspicious behavior. Try to identify how the initial compromise was achieved as well as how the postcompromise activity was performed. Did the adversary leverage legitimate system functions for malicious purposes, i.e., living off the land techniques?

Research the Behavior. Additional research may be needed in order to gain the required context to understand suspicious adversary or software behaviors.

a. Look at the original source reporting to understand how the behavior was manifest in those reports. Additional resources may include reports from security vendors, U.S. government cyber organizations, international CERTS, Wikipedia, and Google.

b. While not all of the behaviors may translate into techniques and sub-techniques, technical details can build on each other to inform an understanding of the overall adversary behavior and associated objectives.

c. Search for key terms on the ATT&CK website to help identify the behaviors. One popular approach is to search for key verbs used in a report describing adversary behavior, such as “issuing a command,” “creating persistence,” “creating a scheduled task,” “establishing a connection,” or “sending a connection request.”

Identify the Tactics. Comb through the report to identify the adversary tactics and the flow of the attack. To identify the tactics (the adversary’s goals), focus on what the adversary was trying to accomplish and why. Was the goal to steal the data? Was it to destroy the data? Was it to escalate privileges?

- a. Review the tactic definitions to determine how the identified behaviors might translate into a specific tactic. Examples might include:

- i. “With successful exploitation, [the activity] would give any user SYSTEM access on the machine.” Tactic: Privilege Escalation [TA0004]

- ii. “Uses the Windows command “cmd.exe” /C whoami.”4 Tactic: Discovery [TA0007]

- iii. “Creates persistence by creating the following scheduled task.” Tactic: *Persistence *[TA0003]

- b. Identify all of the tactics in the report. Each tactic includes a finite number of actions an adversary can take to implement their goal. Understanding the flow of the attack can help identify the techniques or sub-techniques that an adversary may have employed.

- a. Review the tactic definitions to determine how the identified behaviors might translate into a specific tactic. Examples might include:

Identify the Techniques. After identifying the tactics, review the technical details associated with how the adversary tried to achieve their goals. For example, how did the adversary gain the Initial Access [TA0001] foothold? Was it through spearphishing or through an external remote service? Drill down on the range of possible techniques by reviewing the observed behaviors in the report. Note: if you have insufficient detail to identify an applicable technique, you will be limited to mapping to the tactic level, which alone is not actionable information for detection purposes.

a. Compare the behavior in the report with the description of the ATT&CK techniques listed under the identified tactic. Does one of them align? If so, this is probably the appropriate technique.

b. Be aware that multiple techniques may apply concurrently to the same behavior. For example, “HTTP-based Command and Control (C2) traffic over port 8088” would fall under both the Non-Standard Port *[T1571] technique and *Web Protocols [T1071.001] sub-techniques of Application Layer Protocol [T1071]. Mapping multiple techniques to a behavior concurrently allows the analyst to capture different technical aspects of behaviors, relate behaviors to their uses, and align behaviors to data sources and countermeasures that can be used by defenders.

c. Do not assume or infer that a technique was used unless the technique is explicitly stated or there is no other technical way that a behavior could have occurred. In the “HTTP-based Command and Control (C2) traffic over port 8088” example, if the C2 traffic is over HTTP, an analyst should not assume the traffic is over port 80 because adversaries may use non-standard ports.

d. Use the Search bar on the top left of the ATT&CK website—or CTRL+F on the ATT&CK Enterprise Techniques web page—to search for technical details, terms, or command lines to identify possible techniques that match the described behavior. For example, searching for a particular protocol might give insight into a possible technique or subtechnique.

e. Ensure that the techniques align with the appropriate tactics. For example, there are two techniques that involve scanning. The Active Scanning [T1595] technique under the Reconnaissance tactic occurs before compromise of the victim. The technique describes active reconnaissance scans that probe victim infrastructure via network traffic in order to gather information that can be used during targeting. The Network Service Scanning [T1046] technique in the Discovery [TA0007] tactic occurs after the compromise of the victim and describes the use of port scans or vulnerability scans to enumerate the services running on remote hosts.

f. Consider techniques and sub-techniques as elements of an adversary’s playbook, rather than as isolated activities. Adversaries often use information they obtain from each action in an operation to determine what additional techniques they will employ in the attack cycle. Because of this, techniques are often linked in the attack chain.

4 Displays user, group and privileges information for the user who is currently logged on to the local system.

Identify the Sub-techniques. Review subtechnique descriptions to see if they match the information in the report. Does one of them align? If so, this is probably the right sub-technique. Depending upon the level of detail in the reporting, it may not be possible to identify the sub-technique in all cases. Note: map solely to the parent technique only if there is not enough context to identify a subtechnique.

a. Read the sub-technique descriptions carefully to understand the differences between them. For example, Brute Force [T1110] includes four sub-techniques: Password Guessing [T1110.001], Password Cracking [T1110.002],* Password Spraying* [T1110.003], and Credential Stuffing [T1110.004]. If, for example, the report provides no additional context to identify the sub-technique that the adversary used, simply identify Brute Force [T1110]—which covers all methods for obtaining credentials—as the parent technique.

b. In cases where the parent of a sub-technique aligns to multiple tactics, make sure to choose the appropriate tactic. For example, the Process Injection: Dynamic-link Library Injection [T1055.001] sub-technique appears in both Defense Evasion [TA0005] and *Privilege Escalation *[TA0004] tactics.

c. If the sub-technique is not easily identifiable—there may not be one in every case—it can be helpful to review the procedure examples. The examples provide links to the source CTI reports that support the original technique mapping. The additional context may help affirm a mapping or suggest that an alternative mapping should be investigated. There is always a possibility that a behavior may be a new technique not yet covered in ATT&CK. For example, new techniques related to the SolarWinds supply chain compromise led to an out-of-cycle version modification to the ATT&CK framework. The ATT&CK team strives to include new techniques or sub-techniques as they become prevalent. Contributions from the community of security researchers and analysts help make this possible. Please notify the ATT&CK team if you are observing a new technique or sub-technique or new use of a technique.

- Compare your Results to those of Other Analysts. Improve your mappings by collaborating with other analysts. Working with other analysts on mappings lends diversity of viewpoints and helps inform additional perspectives that can raise awareness of possible analyst bias. A formal process of peer review and consultation can be an effective means to share perspectives, promote learning, and improve results. A peer review of a report annotated with the proposed tactic, techniques, and sub-techniques can result in a more accurate mapping of TTPs missed in the initial analysis. This process can also help to improve consistency of mapping throughout the team.

MAPPING MITRE ATT&CK INTO RAW DATA

The options described below represent possible approaches to mapping raw data to ATT&CK. Raw data incorporates a mix of data sources that may contain artifacts of adversarial behaviors. Types of raw data include shell commands, malware analysis results, artifacts retrieved from forensic disk images, packet captures, and Windows event logs.

Option 1. Start with a Data Source to Identify the Technique and Procedure. Review the data source (e.g., process and process command line monitoring, file and registry monitoring, packet captures) which is usually collected by Windows event logs, Sysmon, EDR tools, and other tools. Questions that may inform analysis of potential malicious behavior include:

a. What is the object of the adversary’s focus (e.g., is this a file, a flow, a driver, a process)?

b. What is the action that is being performed on the object?

c. What techniques require this activity? This may help narrow down to a subset of techniques. If unknown, skip to step d.

d. Is there substantiating activity that can help narrow down which technique occurred?

- i. Use of known tools (e.g., credential dumping tools such as gsecdump or mimikatz). Note: Adversaries may disguise the use of known tools by changing their name, however, the command-line flags provided will stay the same.

- ii. Use of known system components (e.g., regsvr32, rundll32).

- iii. Access to specific system components (e.g., registry).

- iv. Use of scripts (e.g., files ending in .py, .java, .js).

- v. Identification of specific ports (e.g., 22, 80).

- vi. Identification of the protocols involved (e.g., RDP, DNS, SSH, Telnet, FTP).

- vii. Evidence of obfuscation or deobfuscation.

- viii. Evidence of a specific device involved (e.g., domain controller) and, if so, evidence of unexpected or inconsistent behavior for that device type.

Option 2. Start with Specific Tools or Attributes and Broaden the Aperture. Raw data offers a unique view of an adversary’s actions or tooling. It may be possible to identify their commands via process monitoring event logs, specific file system components that were accessed (e.g., Windows Registry), or even certain software that they used (e.g., mimikatz). An analyst can search the ATT&CK repository to potentially identify techniques or sub-techniques that align with these items. Analysts can also leverage them as a source of further exploration of related techniques. For example, if an adversary created a registry key for persistence in

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Runto execute when a computer reboots or a user logs on (i.e., Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder [T1547.001]), an analyst may be able to explore other behaviors associated with the event. For example, malicious registry entries often masquerade as legitimate entries to avoid detection (Masquerading [T1036]), which is a Defense Evasion [TA0005] tactic.Option 3. Start with Analytics. Detection analytics—or detection rules—are typically operationally implemented within a SIEM platform, which collects and aggregates log data and performs analytics like correlation and detection. The analytics seek to identify malicious adversary activity by analyzing observable events—often a chain of events—within a range of logs, such as VPN logs, Windows event logs, IDS logs, and firewall logs. Through this analysis, detection analytics may provide insight into additional data sources that may contain artifacts of a specific adversary technique.

a. Many organizations share their analytics as open-source material. These include:

- i. Sigma (a standardized rule syntax for SIEMs). Sigma rules contain logic to detect computer processes, commands, and operations. For example, there are multiple Sigma rules related to detecting the credential dumper Mimikatz. Click here for an example of a Sigma rule that detects credential dumping and contains associated ATT&CK techniques and sub-techniques in the tags field.

- ii. MITRE’s Cyber Analytics Repository (CAR). CAR is a knowledge base of rules for detecting a set of ATT&CK tactics, techniques, and sub-techniques. Click here for an example of a CAR analytic (CAR-2020-05-001: MiniDump of LSASS) that detects the minidump variant of credential dumping where a process opens lsass.exe to extract credentials using the Win32 API call MiniDumpWriteDump.

- iii. LSASS Access from Non System Account. Also behavior-based, this rule detects non-privileged processes that attempt to access the LSASS process—a critical step in executing Mimikatz to collect credentials from a system. Click here to view a GitHub entry for this open-source rule, which maps to the associated ATT&CK tactic, technique, and sub-technique.

APPENDIX A: RESOURCES5

The following links provide useful resources for ATT&CK:

MITRE ATT&CK website

MITRE ATT&CK®: Design and Philosophy, revised March 2020

- Provides an overview of ATT&CK’s structure and goals for ATT&CK.

Getting Started with ATT&CK (PDF version)

Introduction to ATT&CK Navigator (video)

Using ATT&CK for Cyber Threat Intelligence.

Finding Cyber Threats with ATT&CK-Based Analytics

ATT&CKcon Presentations

ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise

ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise Covering Cloud-Based Techniques

ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise Covering Techniques Against Network Infrastructure Devices

ATT&CK Matrices for Mobile

ATT&CK for Industrial Control Systems

MITRE ATT&CK Blog (announces version updates)

@MITREattack Twitter (announces webinars)

ATT&CK Training Courses o MITRE ATT&CK Defender (MAD) program (free training and paid certifications)

APPENDIX B: EXAMPLE REPORT INCORPORATING ATT&CK

The following pages contain an example of a finished report that incorporates:

In-line ATT&CK TTP links as part of the narrative to flag the presence of an ATT&CK TTP. In-line ATT&CK mapping helps the reader to understand the activity as they are reading the report.6

Summary ATT&CK tablesthat identify the ATT&CK technique ID, the name, and context (i.e., details about the adversary’s use of the particular technique). Analysts should provide enough information in the context section that the audience can understand the rationale for the ATT&CK mapping and, ideally, what it means for their own organization. Summary tables allow the reader to quickly scan and identify techniques or sub-techniques of concern or interest.

ATT&CK Navigator Visualization to codify the adversary tactics and techniques. Visualizations can be used to 1) summarize all of the adversary’s activities, 2) highlight TTPs that are unique to an adversary, or 3) to compare and contrast multiple adversary TTPs.

Permalinks, which include the version (e.g., https://attack.mitre.org/versions/v8/techniques/T1105/) for all TTP links to ensure these will endure version changes of ATT&CK.

The corresponding parent technique into any reference of a sub-technique. Note: this is an especially good practice when referencing sub-techniques that have the same name.

5 CISA does not endorse any commercial product or service, including any subjects of analysis. Any reference to specific commercial products, processes, or services by service mark, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply their endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by CISA.

6References may include the number and name or simply the number by itself; e.g., “The actor delivered Trickbot via phishing emails (Phishing: Spearphishing Link [T1566.002]).” or “The actor delivered Trickbot via phishing emails [T1566.002].”

TrickBot Malware

SUMMARY

Callout Box: This Joint Cybersecurity Advisory uses the MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK®) framework, Version 8. See the ATT&CK for Enterprise framework for all referenced threat actor techniques.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) have observed a significant increase in spearphishing campaigns using TrickBot malware to target legal and insurance organizations in North America. A sophisticated group of cybercrime actors is luring victims, via phishing emails, with a traffic infringement phishing scheme to download TrickBot.

TrickBot—first identified in 2016—is a Trojan developed and operated by a sophisticated group of cybercrime actors. Originally designed as a banking Trojan to steal financial data, TrickBot has evolved into highly modular, multi-stage malware that provides its operators a full suite of tools to conduct a myriad of illegal cyber activities.

To secure against TrickBot, CISA and FBI recommend implementing the mitigation measures described in this Alert, which include blocking suspicious Internet Protocol addresses, using antivirus software, and providing social engineering and phishing training to employees.

TECHNICAL DETAILS

TrickBot is an advanced Trojan that malicious actors spread primarily by spearphishing campaigns using tailored emails that contain malicious attachments or links, which—if enabled—execute malware (Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment [T1566.001], Phishing: Spearphishing Link [T1566.002]). CISA and FBI are aware of recent attacks that use phishing emails, claiming to contain proof of a traffic violation, to steal sensitive information. The phishing emails contain links that redirect to a website hosted on a compromised server that prompts the victim to click on photo proof of their traffic violation (User Execution: Malicious Link [T1204.001], User Execution: Malicious File [T1204.002]). In clicking the photo, the victim unknowingly downloads a malicious JavaScript file that, when opened, automatically communicates with the malicious actor’s command and control (C2) server to download TrickBot to the victim’s system (Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript [T1059.007]).

Attackers can use TrickBot to:

- Drop other malware, such as Ryuk and Conti ransomware, or

- Serve as an Emotet downloader (Ingress Tool Transfer [T1105]).[1]

TrickBot uses person-in-the-browser attacks to steal information, such as login credentials (Man in the Browser [T1185]). Additionally, some of TrickBot’s modules spread the malware laterally across a network by abusing the Server Message Block (SMB) Protocol (Lateral Tool Transfer [T1570]). TrickBot operators have a toolset capable of spanning the entirety of the MITRE ATT&CK framework, from actively or passively gathering information that can be used to support targeting (Reconnaissance [TA0043]), to trying to manipulate, interrupt, or destroy systems and data (Impact [TA0040]).

TrickBot is capable of data exfiltration over a hardcoded C2 server, cryptomining, and host enumeration (e.g., reconnaissance of Unified Extensible Firmware Interface or Basic Input/Output System [UEFI/BIOS] firmware) (Exfiltration Over C2 Channel [T1041], Resource Hijacking [T1496], System Information Discovery [T1082]).[2] For host enumeration, operators deliver TrickBot in modules containing a configuration file with specific tasks.

Figure 1 lays out TrickBot’s use of enterprise techniques via the ATT&CK Navigator visualization.

Figure 1: ATT&CK Navigator visualization of enterprise techniques used by TrickBot

MITRE ATT&CK TECHNIQUES

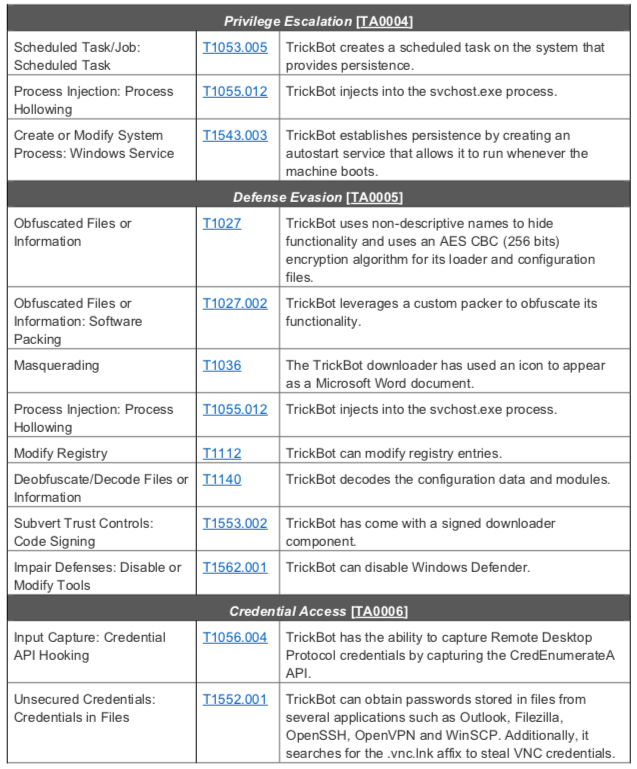

According to MITRE, TrickBot [S0266] uses the ATT&CK techniques listed in table 1.

DETECTION

Signatures

CISA developed the following snort signature for use in detecting network activity associated with TrickBot activity.

alert tcp any [443,447] -> any any (msg:”TRICKBOT:SSL/TLS Server X.509 Cert Field contains ‘example.com’ (Hex)”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,from_server; ssl_state:server_hello; content:”|0b|example.com”; fast_pattern:only; content:”Global Security”; content:”IT Department”; pcre:”/(?:\x09\x00\xc0\xb9\x3b\x93\x72\xa3\xf6\xd2|\x00\xe2\x08\xff\xfb\x7b\x53\x 76\x3d)/”; classtype:bad-unknown; metadata:service ssl,service and-ports;)

alert tcp any any -> any $HTTP_PORTS (msg:”TRICKBOT_ANCHOR:HTTP URI GET contains ‘/anchor’”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,to_server; content:”/anchor”; http_uri; fast_pattern:only; content:”GET”; nocase; http_method; pcre:”/^\/anchor_?.{3}\/[\w_-]+.[A-F0-9]+\/?$/U”; classtype:bad-unknown; priority:1; metadata:service http;)

alert tcp any $SSL_PORTS -> any any (msg:”TRICKBOT:SSL/TLS Server X.509 Cert Field contains ‘C=XX, L=Default City, O=Default Company Ltd’”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,from_server; ssl_state:server_hello; content:”|31 0b 30 09 06 03 55 04 06 13 02|XX”; nocase; content:”|31 15 30 13 06 03 55 04 07 13 0c|Default City”; nocase; content:”|31 1c 30 1a 06 03 55 04 0a 13 13|Default Company Ltd”; nocase; content:!”|31 0c 30 0a 06 03 55 04 03|”; classtype:bad-unknown; reference:url,www.virustotal.com/gui/file/e9600404ecc42cf86d38deedef94068db39b7a0 fd06b3b8fb2d8a3c7002b650e/detection; metadata:service ssl;)

alert tcp any any -> any $HTTP_PORTS (msg:”TRICKBOT:HTTP Client Header contains ‘boundary=Arasfjasu7’”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,to_server; content:”boundary=Arasfjasu7|0d 0a|”; http_header; content:”name=|22|proclist|22|”; http_header; content:!”Referer”; content:!”Accept”; content:”POST”; http_method; classtype:bad-unknown; metadata:service http;)

alert tcp any any -> any $HTTP_PORTS (msg:”TRICKBOT:HTTP Client Header contains ‘User-Agent|3a 20|WinHTTP loader/1.’”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,to_server; content:”User-Agent|3a 20|WinHTTP loader/1.”; http_header; fast_pattern:only; content:”.png|20|HTTP/1.”; pcre:”/^Host\x3a\x20(?:\d{1,3}.){3}\d{1,3}(?:\x3a\d{2,5})?$/mH”; content:!”Accept”; http_header; content:!”Referer|3a 20|”; http_header; classtype:bad-unknown; metadata:service http;)

alert tcp any $HTTP_PORTS -> any any (msg:”TRICKBOT:HTTP Server Header contains ‘Server|3a 20|Cowboy’”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,from_server; content:”200”; http_stat_code; content:”Server|3a 20|Cowboy|0d 0a|”; http_header; fast_pattern; content:”content-length|3a 20|3|0d 0a|”; http_header; file_data; content:”/1/”; depth:3; isdataat:!1,relative; classtype:bad-unknown; metadata:service http;)

alert tcp any any -> any $HTTP_PORTS (msg:”TRICKBOT:HTTP URI POST contains C2 Exfil”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,to_server; content:”Content-Type|3a 20|multipart/form-data|3b 20|boundary=——Boundary”; http_header; fast_pattern; content:”User-Agent|3a 20|”; http_header; distance:0; content:”Content-Length|3a 20|”; http_header; distance:0; content:”POST”; http_method; pcre:”/^\/[az]{3}\d{3}\/.+?.[A-F0-9]{32}\/\d{1,3}\//U”; pcre:”/^Host\x3a\x20(?:\d{1,3}.){3}\d{1,3}$/mH”; content:!”Referer|3a|”; http_header; classtype:bad-unknown; metadata:service http;)

alert tcp any any -> any $HTTP_PORTS (msg:”HTTP URI GET/POST contains ‘/56evcxv’ (Trickbot)”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,to_server; content:”/56evcxv”; http_uri; fast_pattern:only; classtype:bad-unknown; metadata:service http;)

alert icmp any any -> any any (msg:”TRICKBOT_ICMP_ANCHOR:ICMP traffic conatins ‘hanc’”; sid:1; rev:1; itype:8; content:”hanc”; offset:4; fast_pattern; classtype:bad-unknown;)

alert tcp any any -> any $HTTP_PORTS (msg:”HTTP Client Header contains POST with ‘host|3a 20|.onion.link’ and ‘data=’ (Trickbot/Princess Ransomeware)”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,to_server; content:”POST”; nocase; http_method; content:”host|3a 20|”; http_header; content:”.onion.link”; nocase; http_header; distance:0; within:47; fast_pattern; file_data; content:”data=”; distance:0; within:5; classtype:bad-unknown; metadata:service http;)

alert tcp any any -> any $HTTP_PORTS (msg:”HTTP Client Header contains ‘host|3a 20|tpsci.com’ (trickbot)”; sid:1; rev:1; flow:established,to_server; content:”host|3a 20|tpsci.com”; http_header; fast_pattern:only; classtype:badunknown; metadata:service http;)

MITIGATIONS

CISA and FBI recommend that network defenders—in federal, state, local, tribal, territorial governments, and the private sector—consider applying the following best practices to strengthen the security posture of their organization’s systems. System owners and administrators should review any configuration changes prior to implementation to avoid negative impacts.

- Provide social engineering and phishing training to employees.

- Consider drafting or updating a policy addressing suspicious emails that specifies users must report all suspicious emails to the security and/or IT departments.

- Mark external emails with a banner denoting the email is from an external source to assist users in detecting spoofed emails.

- Implement Group Policy Object and firewall rules.

- Implement an antivirus program and a formalized patch management process.

- Implement filters at the email gateway and block suspicious IP addresses at the firewall.

- Adhere to the principle of least privilege.

- Implement a Domain-Based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance validation system.

- Segment and segregate networks and functions.

- Limit unnecessary lateral communications between network hoses, segments, and devices.

- Consider using application allowlisting technology on all assets to ensure that only authorized software executes, and all unauthorized software is blocked from executing on assets. Ensure that such technology only allows authorized, digitally signed scripts to run on a system.

- Enforce multi-factor authentication.

- Enable a firewall on agency workstations configured to deny unsolicited connection requests.

- Disable unnecessary services on agency workstations and servers.

- Implement an Intrusion Detection System, if not already used, to detect C2 activity and other potentially malicious network activity

- Monitor web traffic. Restrict user access to suspicious or risky sites.

- Maintain situational awareness of the latest threats and implement appropriate access control lists.

- Disable the use of SMBv1 across the network and require at least SMBv2 to harden systems against network propagation modules used by TrickBot.

- Visit the MITRE ATT&CK Techniques pages (linked in table 1 above) for additional mitigation and detection strategies.

- See CISA’s Alert on Technical Approaches to Uncovering and Remediating Malicious Activity for more information on addressing potential incidents and applying best practice incident response procedures.

For additional information on malware incident prevention and handling, see the National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 800-83, Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling for Desktops and Laptops.

RESOURCES

CISA Fact Sheet: TrickBot Malware

MS-ISAC White Paper: Security Primer – TrickBot

United Kingdom National Cyber Security Centre Advisory: Ryuk Ransomware Targeting Organisations Globally

CISA and MS-ISAC Joint Alert AA20-280A: Emotet Malware

MITRE ATT&CK for Enterprise

REFERENCES

[1] FireEye Blog – A Nasty Trick: From Credential Theft Malware to Business Disruption

[2] Eclypsium Blog – TrickBot Now Offers ‘TrickBoot’: Persist, Brick, Profit